Several of China’s local government financing vehicles have made recent headlines for their struggles to service debts, rattling the country’s financial markets. But not all LGFVs (local government financing vehicles) are created equal. And while the slowing economy could send some of the weakest issuers to the wall, the fallout so far is contained and doesn’t suggest signs of a systemic crisis.

If a small, provincial borrower in China sneezes, does the country’s entire credit market catch a cold? Even in the current chilly climate, the answer is still no - as this week’s Chart Room shows. Still, that hasn’t stopped a few near misses at smaller borrowers linked to local governments from sending shivers through some corners of China’s bond market.

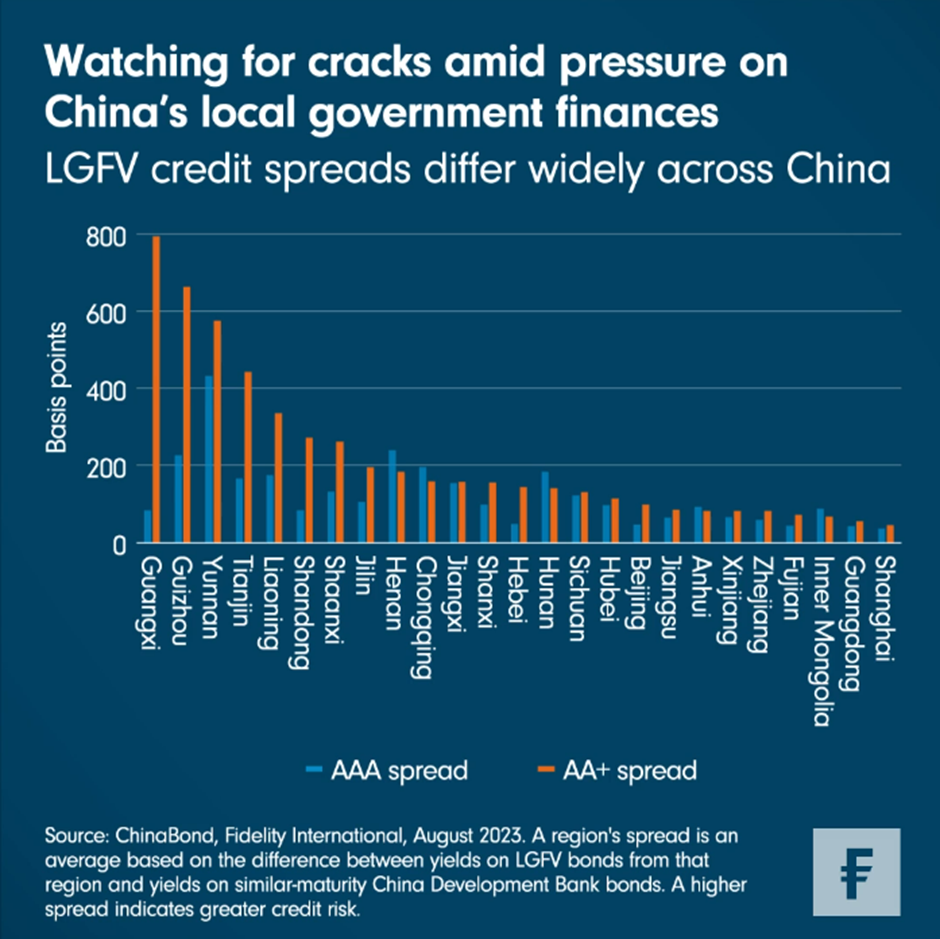

At issue are the health of China’s local government financing vehicles, or LGFVs. These quasi-government borrowers were setup in lieu of a traditional municipal bond market because local governments in China are largely not permitted to sell bonds directly. Today the total amount of LGFV outstanding in China is approaching US$10 trillion and their bonds account for close to half the onshore corporate credit market. So when signs emerge that issuers in the sector are having trouble, investors take notice. There have been several potential red flags of late-- cases of LGFV borrowers coming under stress in provinces like Yunnan, Guangxi, Guizhou, and Inner Mongolia. And while the market has been quick to price in elevated risk in the affected localities, we are not seeing signs that it is spreading to China’s bigger or better-financed regions or borrowers.

The forest for the trees

Consider the recent movement in credit spreads of bonds issued by LGFVs across different Chinese regions. The chart shows clearly how credit differentiation is rising in China, especially in those provinces with the smallest economies, slowest growth rates or heaviest debt loads relative to their ability to repay. In such regions, the spreads - or yield premium over government bonds of a comparable maturity - have surged for weaker-rated credits. But beyond these regions, the spreads on LGFV bonds have barely moved, suggesting investors see the collateral damage as being effectively contained.

Our base-care scenario is that Chinese banks, which are typically the biggest bondholders as well as loan providers for LGFVs, will allow them to roll over their existing debts, although we estimate that 10 to 15 per cent of LGFVs may eventually face debt restructuring.

Moreover, China plans to let local governments issue about 1.5 trillion renminbi (US$206 billion) in “refinancing bonds” to repay LGFV debts, according to Chinese media reports this week. If confirmed, such debt swaps would allow a partial transfer of credit risks from LGFVs to their associated local governments. The arrangement may also help some LGFVs to lower their borrowing costs and lengthen their repayment periods.

The wheat and the chaff

In this environment, we see LGFVs in weaker provinces and with bond yields above 6 per cent as more vulnerable, as their funding costs are less sustainable. This is backed up by the increasingly clear trend of credit differentiation between regions. At the same time, we see other risks continuing to weigh on the market. Weakening land sales amid China’s property downturn have been a key contributor to LGFV stress. While many LGFVs, especially those in poorer regions, used to rely on land sales for a big portion of their income, they now struggle to find new sources of revenue.

With risks like these in mind, we think investors should exercise caution and steer clear of LGFVs with high leverage and high funding costs, especially those in regions where deflation risks are highest, or where land sales continue to deteriorate. While the broader market may yet avoid catching this cold, the hardest hit places are looking decidedly frosty.