It’s become a post-pandemic truism that emerging markets (EMs) are further ahead in their economic cycle than developed ones. Many had more recent experience of managing inflation, and have done a better job of containing this latest bout.

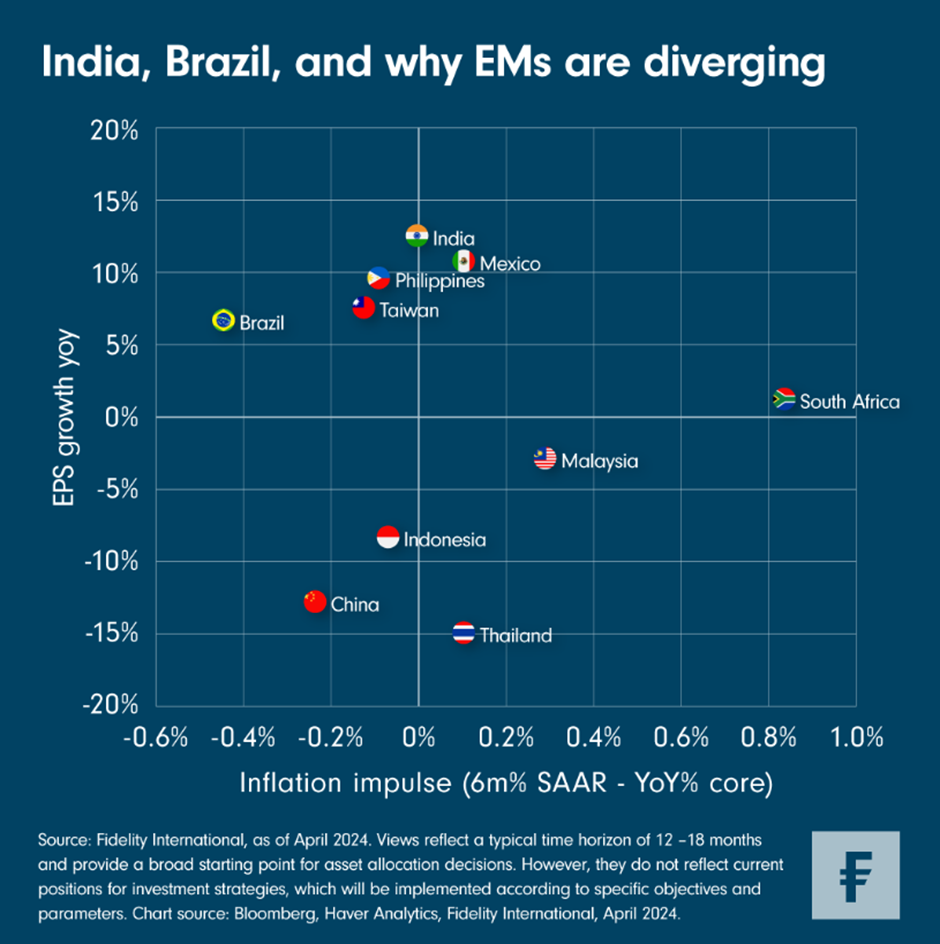

But the picture is not uniform across EMs. This week’s Chart Room highlights some economies that are running ‘too hot’ (towards the top right of the chart), those that are ‘too cold’ (bottom half), and the ones that sit happily in the ‘goldilocks’ zone of disinflationary growth (towards the top left).

‘Too hot’

Mexico has positive growth dynamics, as shown by expectations of positive earnings per share (y-axis). But it continues to suffer from stubborn domestically-driven inflation. The ‘inflation impulse’ metric (x-axis) is captured by subtracting year-on-year core inflation from the seasonally adjusted annualised rate, with a positive value indicating that price pressures are picking up.

Stubborn core inflation (hovering just below 5 per cent in Mexico, with service-sector inflation even higher) has kept interest rates high at 11.25 per cent. And although America’s largest trading partner has benefitted from near-shoring trends, the prospect of a new government in the US and further tariff hikes could turn the temperature higher still.

‘Too cold’

Some EMs meanwhile are flirting with outright deflation, as evidenced by weak earnings growth expectations. Residing in this ‘too cold’ category is China. Arguably the country has moved into another cycle altogether owing to its recalibration towards enhanced production capacity and manufacturing supply chain upgrades, which has led to over-capacity in certain areas. Meanwhile the beleaguered property sector and reticent consumer sentiment continue to stunt end-demand.

China is not totally alone among EMs. Thailand, for instance, has also been facing negative consumer price inflation and weak corporate earnings, with no sign of a pick-up in momentum. Growth here is even more muted than in China, yet the Bank of Thailand insists that the problem is not structural and is reluctant to provide much support.

‘Just right’

Each market has its own story to tell. Among our top picks today are the strong near- and long-term equity stories in India, and the high real yields offered in Brazilian fixed-income markets.

India is firing on all cylinders after a decade-long economic reform push. Purchasing managers’ indices remain the most expansionary across all EMs. New orders are still strong and demand looks robust.

Valuations are arguably beginning to look stretched, meaning that this is a good time to look towards banks and other relatively cheap parts of the Indian market that will benefit from the country’s strong fundamentals and long-term growth prospects.

Brazil, meanwhile, moved particularly quickly to contain inflation in 2022 prior to a solid GDP expansion in 2023. It continues to experience relatively controlled inflation, with a decent growth outlook.

But despite Brazil’s obvious ‘goldilocks’ credentials, there are political uncertainties. Earlier this year, the all government-appointed board members of petroleum giant Petrobas voted down a proposed extraordinary dividend payout. The suggestion that President Lula had intervened to push management to reinvest in the company instead has led to volatility in

Brazilian stocks since March. Yet the country’s solid fundamentals remain, and price movements now arguably present an opportunity for discerning EM investors.

It serves as a reminder that emerging markets rarely tell a simple tale. Dividing them up based on their growth and inflation profiles is an important part of asset allocation. But the real work comes in appreciating each country’s idiosyncrasies.