Central banks have found themselves in a policy paradox through much of 2022, fighting the worst inflation in decades and recessionary threats at the same time. Only in recent weeks did hopes mount for prices plateauing and the Federal Reserve (Fed) pivoting. As we head into 2023, Chart Room takes a look back at the year in charts that best captured the inflationary wave.

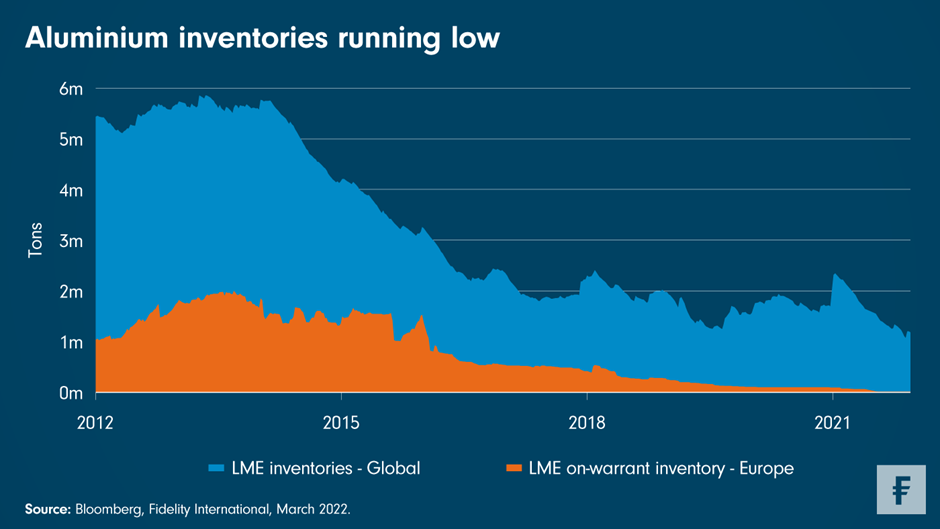

The year began with price hikes exacerbated by Russia’s war in Ukraine, which caused severe disruptions to commodity and energy markets. While much attention was focused on the supply of oil and gas, Fidelity International’s equity analyst James Richards made a chart in March to show a scarcity crunch for aluminium and underscored the risk of extreme volatility in commodity prices ahead.

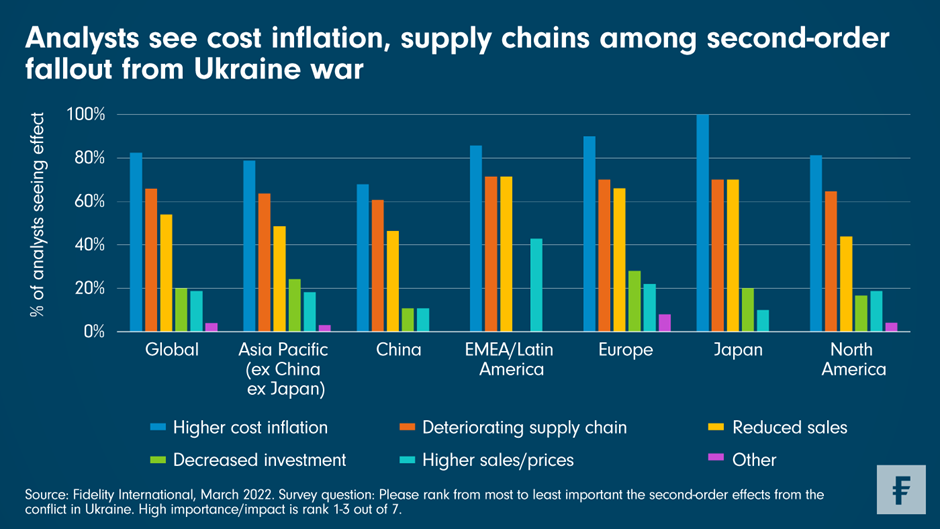

As the war’s appalling casualties grew, its knock-on effects for the global economy became clearer, with higher costs and further disruption to supply chains among the biggest immediate impacts, as Fidelity International’s monthly analyst survey documented back in March. Of the 147 analysts surveyed worldwide, some 82 per cent rank higher costs as a major second-order effect of the war, providing an early warning of severe inflationary pressure in 2022.

We then examined other structural factors contributing to broad and sticky inflation globally. As Fidelity portfolio manager Timothy Foster wrote in April, China-US trade disputes and the fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic both worked against a globalising trend which had been key to lowering costs.

Geopolitical tensions weakened global imports and exports in recent years, while supply chains came under great pressure in the pandemic, forcing companies and governments to reflect on their regional dependencies. Then came Russia’s war which exacerbated this trend of deglobalisation. Foster’s chart illustrated a decline in global trade after years of expansion.

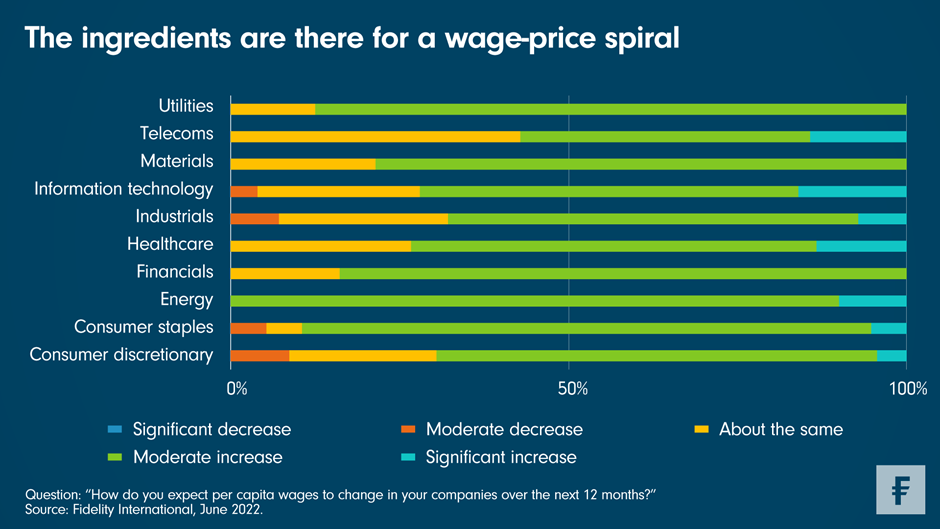

As inflation picked up in the second quarter, our analysts correctly anticipated a wage-price spiral that invoked the spectre of 1970s stagflation. Nearly 80 per cent of Fidelity analysts said in a June survey that they expected to see wage growth over the next 12 months at the companies they cover. These findings provided on-the-ground evidence of what seemed to have spooked central bankers.

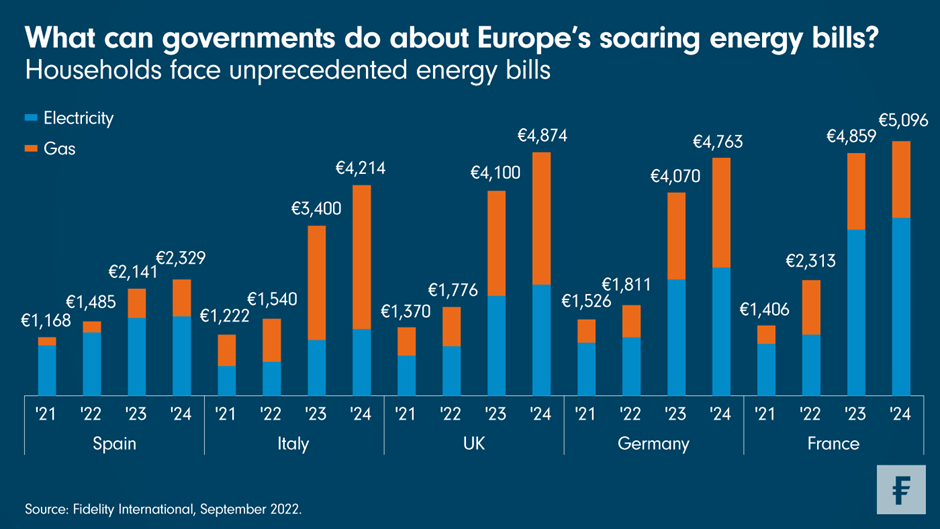

Another toll of inflation were Europe’s soaring energy bills for households. In September, Fidelity portfolio manager Alexander Laing shared his estimates of how consumer energy bills in the largest European economies could climb in the absence of government intervention. “What matters are not so much the specific numbers but the huge scale of these increases,” he wrote. “The burden on consumers and the effect on inflation - for example, via demands for higher wages or firms passing on higher costs - are so great that it is reasonable to expect some form of intervention from government.” And indeed that’s what has transpired since.

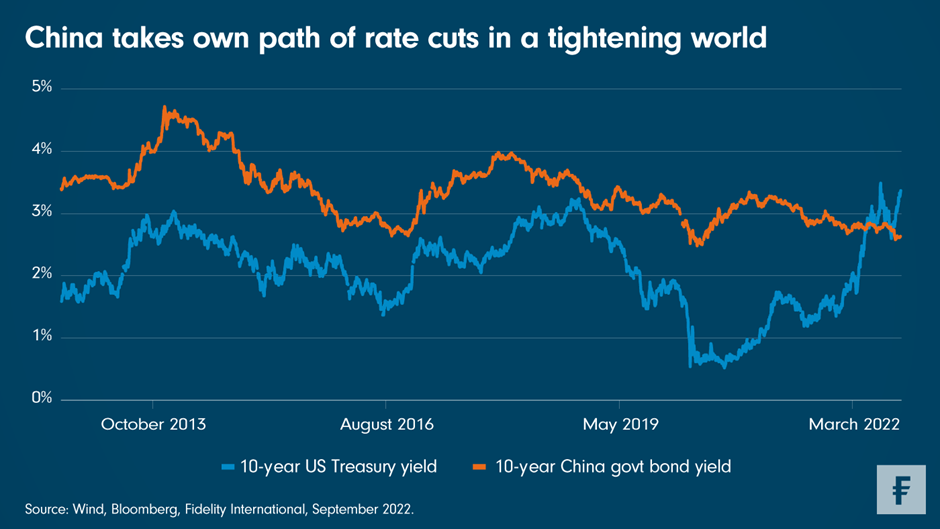

Meanwhile, although inflation forced much of the Western world to tighten, China was dancing to a different tune and retained room for further easing. As Fidelity’s multi-asset portfolio manager Taosha Wang wrote in September, China had bucked the US-led trend towards higher rates, and the resulting yield divergence had huge implications for fixed-income investors and currency markets globally.

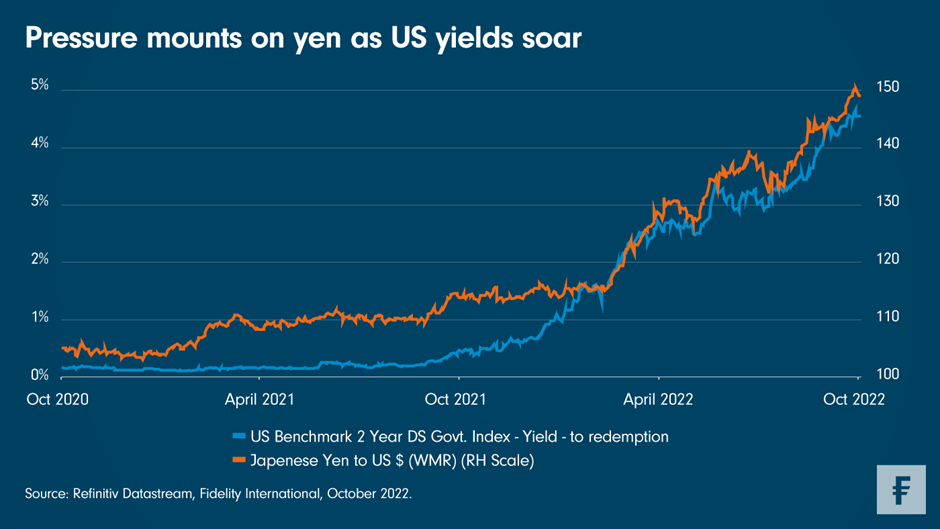

Elsewhere in Asia, the yen came under fire from a strong US dollar and high energy costs, which served to erode Japan’s trade balance as an energy importer. A commitment to yield curve control and ultralow interest rates put the country in a difficult position amid rising inflation. In October, Fidelity portfolio manager Charlotte Harrington highlighted a widening gap between US and Japanese interest rates, and discussed the classic impossible trinity facing Japan.

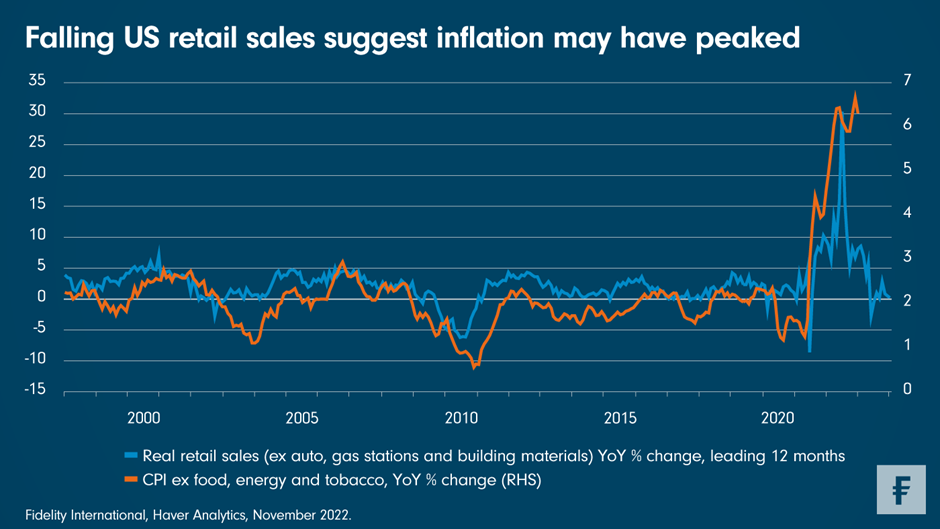

In the fourth quarter, inflation finally showed signs of slowing, kindling hopes for the Fed to pivot away from rate hikes - perhaps by moderating the pace or scale of hikes even while talking tough on their terminal levels. In November, our global macro strategist Max Stainton offered an argument that we may have already seen the peak of US price hikes.

Where retail sales lead, consumer prices tend to follow. Using retail sales as a proxy for overall economic demand, Stainton estimated that US core CPI could fall from 6.3 per cent in October to around 2 per cent by the end of 2023.

Hopes for milder inflation have buoyed both equities and bonds in recent weeks, striking a less hawkish note as we look ahead to 2023. Over the longer term, though, we expect inflation to stay above the Fed’s 2 per cent target, driven by structural factors such as decarbonisation, deglobalisation and debt.